|

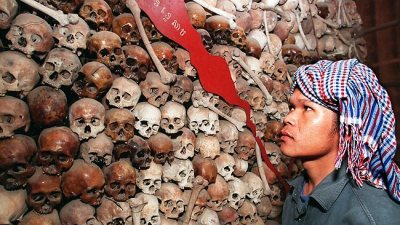

| A Cambodian at the Tuol Sleng (formerly S-21 prison) Museum in Phnom Penh looks at some of the thousands of skulls and bones of 1.7 million Khmer Rouge victims. (Source: Supplied) |

November 29, 2011

By MICHAEL SHERIDAN, PHNOM PENH

The Times

THE trial of three elderly leaders of the Khmer Rouge will hear harrowing new evidence next month about how the revolutionary movement emptied Cambodia’s cities and killed 1.7 million of its people.

“You will hear evidence concerning the inner workings of the regime which you will not have heard before,” said Andrew Cayley, the British co-prosecutor at the tribunal.

Cayley has become a prominent figure in Cambodia after making a searing speech of indictment last week in which he cited the Nuremberg trials of the Nazis and scorned the defendants’ claims that they were not to blame. “They took from the people everything that makes life worth living: family, faith, education, a place to rear one’s children, a place to lay one’s head,” he told the court as the three men sat unmoved. “They are the three most senior living members of a really terrible regime,” continued Cayley, 47, who moves around Phnom Penh under police protection. “It was a different type of killing, but when you look at the Holocaust and you look at this, there is a similarity in the sense of the numbers and also the organisation. It was done in a different way, but it was highly organised and centralised in much the same way.”

The Khmer Rouge won a civil war in 1975 and turned Cambodia into an ultra-radical experiment in communism until they were driven from power in 1979 by a Vietnamese invasion.

The next phase of the trial will concentrate on how they drove the whole population into the countryside and executed anyone connected with the defeated government, which had been backed by the US.

The court was read an account of the exodus from Phnom Penh by Jon Swain of The Sunday Times, one of a handful of correspondents who stayed on to report the fall of the city.

Cayley said drivers, messengers, bodyguards and telegram clerks would place the trio at the scenes of the crimes.

The three old men looked impassive when details of cannibalism, torture, disembowelment and beatings were laid out by the Cambodian co-prosecutor, Chea Leang. She said women had their ears and noses torn off, then guards cut out their livers to fry and eat. Toddlers were beaten to death by swinging them against a tamarind tree. A pregnant woman was dropped into the foundations of a bridge and buried alive.

Even after decades of trying to forget, Cambodians expressed pain on hearing such things.

The three men in the dock are unrepentant and have decided to turn the trial into a platform for their cause.

Khieu Samphan, 80, the French-educated professor who was the Khmer Rouge “head of state”, spoke fiercely in his own defence, denying the charges as “absurd” and justifying his actions as “patriotic”. He was a figurehead who had nothing to do with murder. His lawyer, the French radical Jacques Verges, who acted for the Venezuelan terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal, compared the prosecution case to a novel by Alexandre Dumas and denounced the US for its secret bombing of Cambodia in the 1970s.

A second defendant, Nuon Chea, 85, who was “‘Brother No 2″ to the Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, who died in 1998, said the Khmer Rouge were nationalists who protected Cambodia from foreign plots. He claimed that black-clad agents of the fallen government had carried out the killings in Phnom Penh and said he had wanted “to build Cambodia as a society that was clean and independent”.

The third man on trial, Ieng Sary, 86, the foreign minister who purged the elite of his own ministry, sat silent, his skin stretched like parchment over his gaunt face, as the indictment was heard.

Of all the surviving leaders, he knows most about the Khmer Rouge’s alliance with China and its secret dealings with the West later on. But his only words were to plead ill health and to claim he had received a royal pardon from King Sihanouk and could not therefore be tried.

In fact, as prosecutors admit, the passage of time is the enemy of justice. Fears that the defendants will die led the court to divide the case into “mini-trials”. This present one may take two years.

That is why prosecutors are still trying to get their fourth defendant – the only woman charged with genocide – into court. Ieng Thirith, 79, the wife of Ieng Sary, was the Khmer Rouge’s social affairs minister. She studied Shakespeare at the Sorbonne and became the first Cambodian to hold a degree in English literature.

So far she has been ruled unfit for trial due to Alzheimer’s disease. But, according to court transcripts, the medical evidence is not conclusive.

The defendants have been held at a special detention centre since 2007, where they can receive medical care and family visits.

The court is made up of Cambodian and international judges sitting as an Extraordinary Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia. It can impose a maximum sentence of life and so far has completed only one case: “Duch”, the jailer at the regime’s Tuol Sleng killing centre, was sentenced to 35 years, reduced to 19 on appeal. So far it has cost $US149 million ($151m).

No comments:

Post a Comment